A History of Equestrian Helmet Awareness and Use in the United States

By Drusilla Malavase, past Chair of the ASTM Equestrian Protective Headgear Committee and past USPC Safety Committee Chair

When the United States Pony Clubs was founded in 1954 based on the model of the British Horse Society and The Pony Club. The Pony Club’s original Manual of Horsemanship was published in 1950, and their Instructor’s Handbook followed in 1955. Both were adopted by USPC, and lesson procedures included a required inspection to “Check that the rider’s hat and footwear comply with the current official safety rules.” At the time, riding “hats” were just that—items of apparel. The traditional velvet hunt caps of the day had no safety harness or retention system, and offered no actual protective qualities.

The Effort to Improve Safety

Fast forward to the 1970s, when the USPC Board of Governors led by Board President Rufus Wesson established a task group to search for a source of improved riding helmets, since they were receiving reports of increasing numbers of serious head injuries to USPC members. In 1978, an Advanced-level event rider wearing an unsecured show helmet was photographed during a fall, and the photo also showed the helmet on the ground before the rider landed and was hit on the head by a falling jump rail. The front-page story was reprinted and led to calls for action from Clarke Cassidy, a board member of the United States Combined Training Association (USCTA; now the United States Eventing Association, or USEA).

USPC and USCTA sponsored a meeting in January of 1979 attended by equestrian sports leaders, helmet manufacturers, lawyers, doctors, insurance representatives, competition managers, engineers, bio kineticists and members of the equestrian media. From that meeting came the help of the United States Polo Association, who offered permission to use their newly completed helmet standard. Wayne State University’s National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment (NOCSAE) football helmet standard was also offered, as was the use of the Snell Foundation’s testing lab to test existing equestrian helmets from various other countries.

As the USPC’s new Ad Hoc Safety Committee put together a draft of a standard for protective equestrian headgear, a western New York test laboratory kindly agreed to test prototype helmets and those that passed its provisions were publicly listed. Several equestrian sport governing organizations rewrote their competition rules to require the use of the listed products. This proved to be a controversial move, and it became obvious that the committee needed a more formal procedure and more research.

Groups who used the list included six breed clubs, three instructor certification groups, 13 horse sports groups, three horse industry organizations and welfare groups, one insurance and safety advocate, four youth groups, and five national/international organizations, including those from the United States, Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the Fédération Equestre Internationale (aka, the International Equestrian Federation, or FEI).

The American Society for Testing and Materials (now ASTM International) hosted an exploratory meeting, and in August 1984, the first meeting was held by members of the 1979 meeting and additional component manufacturers, standards editors, consumer safety activists, and testing lab professionals.

By 1988, and six drafts later, F1163-88 was completed as an internationally recognized standard, unique in its partnership with the Safety Equipment Institute (SEI), which provided the testing certification by impartial third-party labs and a quality-control oversight program. Members of the Equestrian Protective Headgear Subcommittee also worked on a base standard for other sports helmets, called F1446. The resulting standards were developed much more quickly than F1163 since they had the advantage of being able to customize from a successful example.

The Era of Helmet Controversy

From January 1990 and into the new millennium, awareness of F1163 and helmet development was not without controversy; the more criticism it generated during “The Riding Helmet Wars,” the better, since it helped gain attention and created an opportunity to educate within the horse industry. One example published in The Chronicle of the Horse in January 1990 mentioned that the publication was getting a lot of reader correspondence that was complaining about the bulk and weight, the difficulties of fitting, the cost, the retention system, and the lack of availability. The writer posed the question, “Why, in the age of miniaturization and high technology, did these new helmets have to be so bulky and unbecoming?”

As time passed, helmets have evolved. F1163 was first published in 1988. By May of 2015 (27 years later), the SEI listed 18 manufacturers of certified equestrian helmets. The list of model numbers was six pages long. By June of 2023 (35 years later), the SEI lists 21 manufacturers of certified equestrian helmets. The list of model numbers is 16 pages long.

Today, certified helmets have become the norm in sporthorse disciplines and acceptance has grown. In March of 2010, Olympic dressage rider Courtney King-Dye, who was riding without a helmet, suffered a traumatic brain injury and was in a coma for a month after the horse she was riding tripped and fell. The incident sparked a wave of international helmet awareness and support, including campaigns such as Riders4Helmets. Several months after King-Dye’s accident, eventer Allison Springer, a graduate of Fox River Valley Pony Club, made headlines as the first rider to wear a helmet in the dressage phase of the Rolex Kentucky CCI5* instead of the traditional top hat favored by most riders in international competition at that time. By 2021, the Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI) required protective headgear while riding and during the marathon phase of combined driving events.

Now helmet options go way beyond basic black. It’s possible to buy helmets covered in bling to match bling browbands and bling stirrups…to customize helmets in a zillion colors or with insets of your flag, or to feature a halo look in rose gold. There are also plenty of styles with a western aesthetic available, although helmet use among western riders has been slower to catch on.

Today’s Helmet Hot Topics

Here are some of the current hot topics surrounding helmet technology, fit, and testing standards.

- Helmet standard committees disagree on which country’s equestrian helmet standard tests reflect “real world impacts” on “real world” surfaces.

- Is the best standard the one that features the most internal tests, or is it more important to address the ones that test for the kinds of impacts that are most likely to result in serious injuries?

- Where is the research to help decide the priorities? Fortunately, thanks to Virginia Tech’s Star Rating System, many of these questions are being addressed.

- Where is the current research that compares the different sections of the current versions of: U. S. Snell E 2016, 2021; U.K. PAS 015; ASTM F1163-15 SEI Certified; Euro VG 1? (In 1999, the Mark Davies Injured Rider Foundation sponsored the UK Government Transportation Research Laboratory to do comparison testing of crush resistance, penetration protection, small size helmets, and different riding surfaces; A summary of the testing is still available for study.) On May 8, 2000, Canada’s biokinetics test facility compared helmets from the U.S., U.K. and Australia/New Zealand, taking into consideration the differing weather conditions of the three environments.

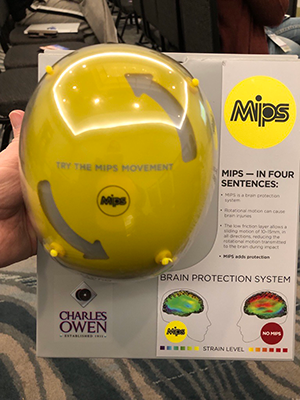

- The past two years have seen the addition of the MIPS system added to helmet products by a variety of manufacturers worldwide. MIPS is a brain protection system within the helmet that is designed to reduce the rotational motion transmitted to the brain during impact. Since this addition has several years of use for bicycle and skiing helmets, it is likely that equestrian helmet committees will be discussing the addition of a test method to include in the future. There are several existing studies available for consideration.

- A major amount of mainstream publicity this year has addressed the question as to how to accommodate riders with long hair worn in ethnic traditional style who compete in classes that require specific standard helmets.

- In February 2023, the Consumer Product Safety Commission announced a formal recall of the Ovation Protégé equestrian helmet, which did not pass SEI certification. No injuries have been reported, and replacements or refund have been facilitated.

- In February 2023, Frantisi Incorporated of Barrie, Ontario, Canada voluntarily notified its distributers that two of its models from several years ago, First Lady and Little Lady helmets developed broken visors during use under cold conditions and could possibly present a sharp edge as a rider hazard. Frantisi offered to replace the visors on these helmets within two years of the date of production. If a rider fall causes the break, the safety rules in place for EN1384:2017 and ASTM F1163-15 require that the helmet be replaced.

- It has been many years since the last recall of an ASTM F1163 helmet, and it is encouraging that the recall system, which is part of SEI certification, is making every effort to avoid injury to our riders.