The Quality of the Gaits

An excerpt from Jane Savoie’s new book Dressage Between the Jumps,

published by Trafalgar Square Books / HorseandRiderBooks.com.

Rhythm should be first and foremost in your mind when riding. No matter what you’re doing—leg-yields, advanced lateral work, counter-canter, flying changes—always check that the rhythm stays regular. That means your horse has equal spacing between the four steps of a stride of walk, the two steps of a stride of trot, and the three steps of a stride of canter.

Working in a regular rhythm will not only make your dressage work more effective but will help you when you jump. That’s because once you have a regular rhythm and stride, you’ll develop an eye for seeing a distance to a jump. Then you can adjust the length of stride in that regular rhythm to suit the type of fence you’re jumping.

IMPROVE THE QUALITY OF THE WALK

Even though you do the majority of your jumping in the canter, practicing exercises in the walk and trot first gives you time to learn how to coordinate the aids. It also gives your horse a chance to understand the exercise without dealing with the speed of the canter. Let’s have a look at what makes up high-quality gaits.

A stride of walk is made up of four steps. Starting with the outside hind, the sequence of legs in one walk stride is: outside hind, outside fore, inside hind, inside fore. The length of the space between each step should be the same.

In a good medium walk:

• The rhythm is regular.

• The horse over-tracks by stepping with his hind feet in front of the tracks made by the front feet.

• He has enough activity to easily propel him-self into an extended walk. You don’t have to “rev him up” first.

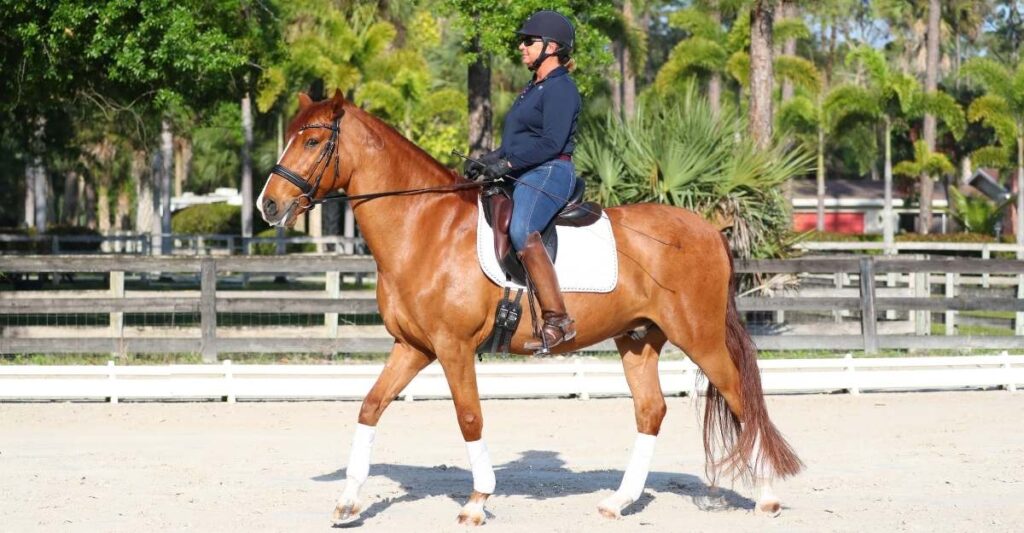

Fig. 1: Say “one” each time you feel the horse’s outside hind foot on the ground. So while riding to the right, as shown here, the rider says “one” each time the horse’s left hind foot is on the ground.

Feel the Rhythm in the Walk

Here’s an exercise to help you feel a regular rhythm with equal spacing between each of the four steps.

- At the walk in a fenced arena, close your eyes so you can tell when the horse’s outside hind foot is on the ground. When the out-side hind foot is on the ground, the horse’s outside hip is higher, so you’ll feel your out-side seat bone or hip either being raised or pushed forward. If it’s hard for you to feel it, ask a friend to watch you ride and call out, “One, one, one,” each time the outside hind foot is on the ground. Your ground person can either watch the foot or look at the hip and say ”one” during the moment when the hip is at the highest point. As she says “one,” notice how that point of the movement feels through your seat bone or hip. Every rider describes the feeling differently.

- See if you can identify when the outside hind foot is on the ground without your ground-person’s help, but ask her to stay with you so she can confirm that you’re saying, “One,” when the outside hind is on the ground as opposed to being in the air. If you aren’t saying it when the outside hind foot is on the ground, have her count it again for you so you can identify the movement—and then try it on your own again.

- Once you can identify the first step, add in the other feet as they come to the ground. The timing of your counting should sound like an even, “One, two, three, four; one, two, three, four; one, two, three, four.” This timing is a regular four-beat walk (fig. 1).

Fixing a Lateral Walk or Pace

If you hear something like, “One, two…three, four,” your horse’s rhythm isn’t regular. When the legs on the same side move too closely together, the walk is called “lateral.” If the rhythm degenerates further and the legs on the same side move together so you count only two beats in the walk, the horse is “pacing.”

Both a lateral walk and a pace are usually caused by tension and stiffness, especially in the back and neck. However, some horses are actually born with lateral walks. Horses with regular walks also can lose regularity. If your horse has a naturally big over-stride in his walk,it might get lateral if you collect the gait too soon in his training or if you restrict him with your hands. Be sure you have an “elastic elbow” that follows the horse’s head and neck forward and back so you don’t block him (Fig. 2 A & B).

Fig. 2A: Maintain an elastic elbow that follows the movement of the horse’s neck and head forward and back. The horse is restricted by the rider’s elbows. The legs on the same side almost move together so that his walk has become lateral.

Fig. 2B: The rider is following the horse’s neck forward and back with elastic elbows. As a result, the horse’s legs show four distinct beats. Because the horse doesn’t feel restricted by the rider’s hands, he can lengthen and lower his head and neck.

Fig. 3: If your horse’s walk gets lateral, send his hindquarters a bit sideways to “break up” the diagonal pairs of legs.

If your horse’s walk gets lateral, send his hindquarters a bit sideways (Fig. 3). You can leg-yield him in a little or out. If he has more education, do shoulder-fore or shoulder-in.

In all cases, these lateral exercises will break up the legs on the same side so the horse can take four even steps. A ground person can tell you when the walk is pure by noting when she can see the legs on the same side forming the letter “V.”

IMPROVE THE QUALITY OF THE TROT

In a working trot your horse goes forward in balance with even, powerful, elastic steps. He shows good hock action as he moves with impulsion.

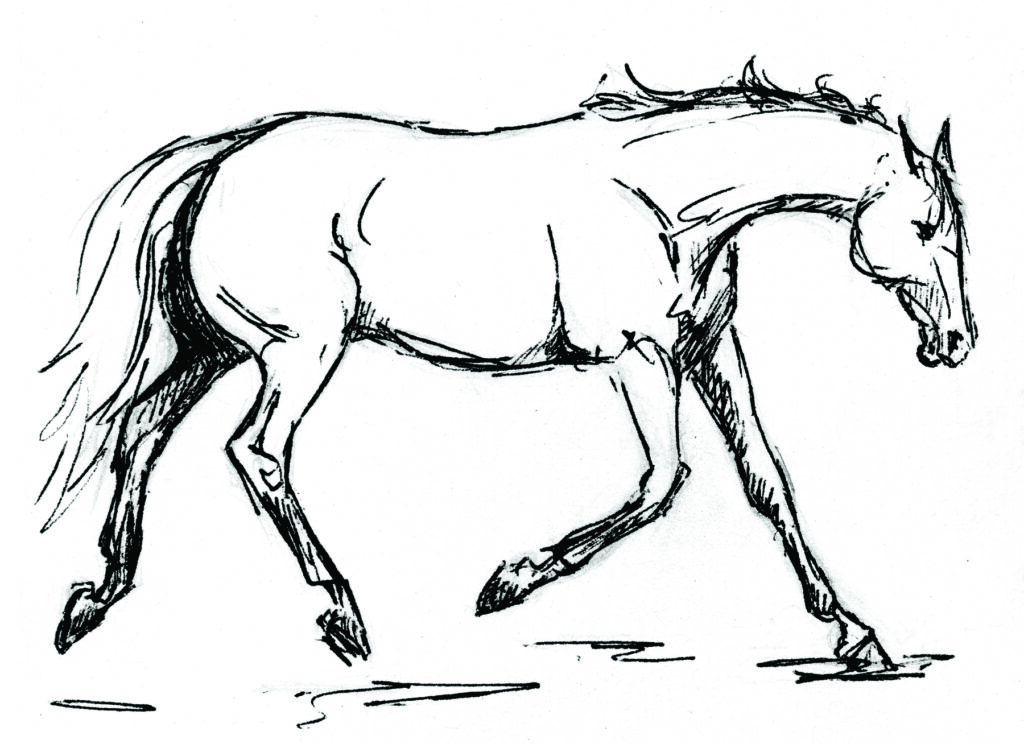

In one stride of the trot, the sequence of legs is: one diagonal pair of outside hind and inside fore moving together, followed by a period of suspension when all four legs are off the ground, then the other diagonal pair of inside hind and outside fore moving together. When doing the exercise, you should hear yourself counting an even, “One…two…one…two…one…two…”If the rhythm isn’t regular, the first thing you should do is check with your vet to make sure there aren’t any soundness issues.

A common fault in the trot is when the horse hurries his steps so that the forefoot comes to the ground before the diagonal hind foot so that two separate hoof beats are heard instead of one (fig. 4). In this case, your horse is carrying most of his weight (and yours) on his shoulders. The solution is to shift the center of gravity back so that his shoulders can be lighter and freer (explained in Dressage Between the Jumps, chapter 10).

Fig. 4: A common fault in the trot is when the horse hurries his steps so that the forefoot comes to the ground before the diagonal hind foot. As a result, two separate hoof beats are heard instead of one beat, which is what you hear when the diagonal pair is moving together.

Another common fault is when the hind foot is put down before the diagonal fore-foot (fig. 5). Again, you’ll hear two separate hoof beats. This happens when your horse is lazy with his hind legs and drags his feet along the ground. Activate the hind legs by doing a lot of quick transitions, not only from gait to gait but also within the gait, like lengthenings and shortenings.

Fig. 5: Another common fault in the trot is when the hind foot is put down before the diagonal forefoot. Again, you’ll hear two separate hoof beats instead of one.

The trot also becomes irregular when one hind leg doesn’t reach as far under the body as the other hind leg. This makes the steps look uneven. You may be able to feel this yourself because there’ll be an emphasis on one of the beats of the trot. You’ll find yourself counting, “One, two, one, two.”

If you can’t feel it, ask a friend on the ground to check that each hind leg steps equally under your horse’s body. As mentioned, check with your veterinarian when this is in question, but also keep in mind that you might just be dealing with a weaker hind leg, a sore back, or your own hand “blocking” the hind leg because you’re pulling back on one rein. If it’s a hind leg issue, there are exercises you can work on to strengthen your horse’s legs. Your horse needs to be equally strong with both hind legs so he jumps straight and doesn’t push off more with the stronger hind leg (fig. 6). If he does, he’ll drift to one side over fences.

IMPROVE THE QUALITY OF THE CANTER

I often see jumpers that have four-beat canters. This four-beat rhythm can create all kinds of problems, such as the horse’s balance being on the forehand and not having a clear enough period of suspension to be able to do a good flying change. To help a horse that has a four-beat canter:

- Ask for a lengthening on a circle. Feel how quickly your seat moves forward and back as your horse lengthens his strides.

- Bring him back to a working canter, but keep the same quick revolutions of your seat that you had during the lengthening. You are “marking” the rhythm and tempo of the canter with your seat.

- Alternate lengthenings and shortenings until the rhythm and tempo of the canter are the same both in the working canter and in the lengthening.

- Now try an exercise like counter-canter, shoulder-fore, or half-pass. In the middle of the movement, quicken the canter with your seat without letting the strides get any longer. Shoulder-fore, in particular, will lower the horse’s croup and elevate his forehand (fig. 7).

- Now place a pole on the ground. Make a long approach to the pole, picking up a slow, flat, four-beat canter during the first part of the approach.

- Without letting the strides get any longer, move your seat as if you are doing a lengthening. See if you can quicken the canter and make it three-beat from the revolutions of your seat alone.

- When you can do this over the pole, try it over a small fence. Remember, you can also approach the fence in shoulder-fore to get the horse’s croup down and his forehand up.

Fig.7 : You can improve the quality of the horse’s canter by riding in shoulder-fore to lower his croup and elevate his forehand.

This excerpt is reprinted with permission from Dressage Between the Jumps by Jane Savoie, published by Trafalgar Square Books; horseandriderbooks.com.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jane Savoie is one of the most recognized names in the equine industry and for good reason. Her accomplishments and the breadth of her influence are impressive. As a dressage rider, she was a member of the United States Equestrian Team, competing internationally, including a position as the reserve rider for the bronze-medal-winning team at the 1992 Olympics. Savoie was the dressage coach for the Canadian 3-Day Event Team at the 1996 and 2004 Olympics, and coached a number of dressage and event riders at the 2000 Olympics. She is the author of many bestselling books and video programs on riding, training, and sport psychology, and is a popular motivational speaker.